Singing on the Off-Beat, Part 2

In my last post I shared some suggestions to help people develop the musicianship skills needed for singing on the off-beat. The second stage of the process is to consider the music that is asking you to deploy these skills and asking if the composer and/or arranger are facilitating your success or creating obstacles.

You see, off-beat passages are a classic example of the kind of thing a notation program can do really well, as it just produces a literal rendition untroubled by the sense-making that the human brain brings to the process of singing. And whilst sometimes (well, quite often) the problem is patchy musicianship skills in the performers, sometimes the problem is also over-optimism on the part of a writer who hasn’t spent enough of their life in rehearsal trying to help people with patchy skills achieve rhythmic security.

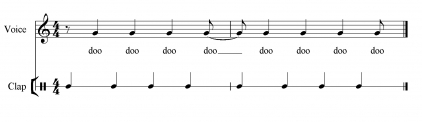

I left you last time with the following exercise, which reproduces the kind of thing you quite often see in a cappella arrangements, and turns out to offer a useful case study to explore this central musical question.

So, the first version, with the clap and t sound I found, as someone with reasonably strong musicianship skills, very easy. But when I changed the percussive t to a sung doo, whilst I still found it easy to keep in tempo, after a while my brain reinterpreted the structure to hear the doo as the on-beat and the clap as the off-beat.

Why would my brain do that? This is a beautiful example of Cooper & Meyer’s principle that musical accent is created by ‘a stimulus marked for consciousness’. (For a more developed discussion of their theory of rhythm as it applies to a cappella, see the series of posts that starts here.) The two alternating, evenly spaced sounds have nothing to differentiate them durationally, but they are quite different both timbrally and kinaesthetically. (The latter is something that Cooper and Meyer, working the largely cerebral tradition of mid-20th-century music theory didn’t consider, but has become increasingly interesting to me as I’ve wandered round the house playing with these rhythms for this post.)

The clap draws attention to itself relative to the t because it takes more movement to create and produces a louder sound, and thus stays perceptually firmly on the downbeat. Whereas the doos stands out relative to the clap due to their continuity of resonance, which one experiences both aurally and as bodily sensation. Hence, my brain accorded it more importance, and re-organised my perception to place it in the structurally more significant role.

So, I thought, what can I do to keep the on-beats perceptually as well as conceptually strong? I found that switching from a clap to a good solid belly-slap with both hands prevented on- and off-beats from switching, as did walking around with steps on the on-beat. The former amplified both the sonic and physical impact of the on-beat, whereas the latter, interestingly, removed the aural impulse pretty much entirely, but was still a very effective provider of metrical structure.

This all illustrates the point at the start of my previous post that singing on the off-beat requires a secure structure of the on-beats so you can bounce off them cleanly and reliably. And so the next question we need to ask is: to what extent is our music providing this structure?

In you’re operating the kind of contemporary a cappella that uses vocal percussion, you’re probably going to be fine, as that offers a clearly audible, timbrally distinctive, and usually amplified metrical structure around which all the other parts can organise themselves. If you’re operating in an a cappella genre that that shares some of the textures and arranging devices of contemporary a cappella but doesn’t use an over-arching percussive envelope to organise your perceptual experience, it’s going to be harder. The latter is the kind of repertoire that the people who got me thinking about this have been grappling with.

So, strategies you might employ could include:

- Inserting some discreet on-beat notes so the singers have something to bounce off, much in the manner of the 3rd and 4th examples in my previous post. As an arranger I do this all the time now because it saves me from having to witness people beating themselves up over their struggles with the off-beats. Entirely selfish of me I realise, but everyone’s life is nicer as a result, not just mine. It won't substitute for developing rhythmic skills in your singers, but it gives everyone a chance if the writer hasn't given you enough metrical scaffolding to work with.

- If there is a part with a strong assertion of metre (often the bass line), nurture the relationship between that part and the off-beat part(s). Have the off-beat parts do the clap & t exercise along with the bassline so they feel how the off-beats fit in with the musical narrative. Then have them sing their line to a quiet staccato ‘dit’; this will help them keep the bassline perceptually strong while they slot in around it. When they can do that and look relaxed at the same time, you can go back to the part as written.

- Leverage the way that physical movement creates perceptually strong metrical structures by using it both as a rehearsal tool and as part of your performance. I know that not all singers are comfortable with physical movement, but I’d also hazard a guess that there is a pretty strong correlation between the capacity to move rhythmically and the capacity to sing rhythmically, so time spent developing movement skills will directly support your goals here.

...found this helpful?

I provide this content free of charge, because I like to be helpful. If you have found it useful, you may wish to make a donation to the causes I support to say thank you.

Archive by date

- 2025 (23 posts)

- 2024 (46 posts)

- 2023 (51 posts)

- 2022 (51 posts)

- 2021 (58 posts)

- 2020 (80 posts)

- 2019 (63 posts)

- 2018 (76 posts)

- 2017 (84 posts)

- 2016 (85 posts)

- 2015 (88 posts)

- 2014 (92 posts)

- 2013 (97 posts)

- 2012 (127 posts)

- 2011 (120 posts)

- 2010 (117 posts)

- 2009 (154 posts)

- 2008 (10 posts)